Cultural schools in our community also deal with COVID challenges

When someone says the phrase “Sunday school,” you probably assume that they are referring to a religious institution. However, growing up, I went to school on Sundays without so much as reading a religious text or praying or learning the word of God as most Sunday schools would have you do.

And this is also true for a considerable, but often overlooked, population of our suburban lives: immigrants and their children. For us, it is common to send our children to Sunday schools not to learn about religion, but to learn our language and culture.

While not all who attend are from immigrant families, many are. I have attended a Chinese school for most of my life, and have gotten used to the routine and rhythm of it. But this year has disrupted it, as it has with many other things, and has had significant impacts on the way it operates.

One person who has experienced these impacts firsthand is Janice Chen, the principal of Tzu Chi Academy’s Chicago school, a Chinese school based in Darien, Illinois.

Most Chinese schools in our area, including Tzu Chi, transitioned to online classes last year. Despite staying open, though, not everyone was able to receive the same education that they always had, and enrollment dropped.

“For a lot of students, online school has made it harder for students to learn, especially for kids who don’t have the environment to speak Chinese at home,” Chen said. Because of this, “kids under five have dropped at much higher rates, as well as CFL students.”

These CFL (Chinese as a Foreign Language) students come from non-Chinese speaking families, and must learn the language from scratch. At most Chinese schools, they are placed in separate programs and classes.

Another difficulty that these schools face is finding teachers. This has long been a struggle, with a neverending shortage, year after year.

This is “first of all due to the fact that most of our teachers work mainly as volunteers […] and second of all, because it is hard to meet new people and potential teachers,” Chen said.

COVID has only exacerbated this situation, causing some classes to be unavailable. At Tzu Chi, Chen has had to take on the role of teacher on top of being a principal.

While the effects of COVID have been mostly consistent for all Chinese schools in our area, Tzu Chi has managed to escape the worst of it. Chen attributes this to the community-based nature of the school, as “all of [their] teachers are parents. Other schools don’t do this, so their teachers don’t have the same drive to help their students continue.” Tzu Chi is a tight-knit community, where people are “like family”.

Tzu Chi also has the benefit of being more flexible, because they “only go to school one day a week… [unlike] public schools which are open more days a week and handle more kids,” Chen said. Additionally, the “parents are all very cooperative” with the school’s safety measures, making it easier on administrators.

The aforementioned safety measures, which are stricter than many other schools and are only possible because of the private nature of the school and the flexibility that comes with it, include requiring vaccinations for all students above 12 years old, and temporarily switching to online classes for any cases of COVID within the school.

Tzu Chi has recently had a case and has been forced to move online. The COVID case may not have been contracted at the school, as kids “don’t just come to our school. They also go out and to other schools,” Chen said. However, the school remains confident in the safety of their students, a stance that is backed by their safety measures, as well as “small class size” and “limited exposure due to short classes held only once a week,” according to Chen.

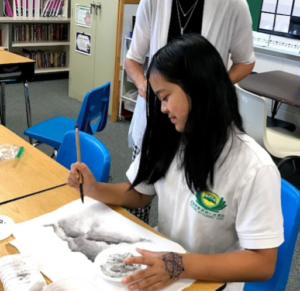

Despite having already graduated from chinese school over a year ago, I’m still involved in the school as a teacher’s assistant, and unsurprisingly, the environment of in-person Chinese school is vastly different from that of online school. While this is obvious, it’s hard to convey the difficulties that many other people at this school faced when we were cut off from this community after graduating.

It’s especially hard because it isn’t a community that exists within a well-defined area, but rather one that is scattered amongst different towns, schools, and ages, which only really meets within these weekly get-togethers. It’s a school made not only of educators and students, but of graduates, parents, and grandparents, a place where people can share their culture in a public space with people who understand, rather than confining that part of their identity to the inside of their homes.

It is this communal nature that has been both a hindrance and a strength during COVID, but ultimately, the success of these Chinese schools could serve to prove that the ties of culture and background still bind us together, even when they are stretched by physical barriers.